|

The Orquesta Sinfonica de Galicia is one of my favorite concert orchestras to watch on YouTube. They present full length concerts in excellent sound and high-quality videography - with expert, knowledgeable camera operators who zoom in on the appropriate musicians at the appropriate times, corresponding with what we’re hearing. Watching Dima Slobodeniouk build this orchestra through the years into an ensemble of real stature has been rewarding to witness. I have always credited his success for his no-nonsense presence on the podium - eschewing ostentatious mannerisms and extravagant flailing about, instead focusing on a very crisp baton which is easy to follow and allows the orchestra to be instantaneously responsive to his every gesture. He consistently draws precision from the orchestra, and elicits weight and real power when called for.

Dima Slobodeniouk (hereafter referred to, simply, as “Dima”) has recorded several albums for BIS (most often with his other orchestra, the Lahti Symphony), but I was excited to see this Stravinsky release is with the Galicia. And they acquit themselves brilliantly. They can stand proudly alongside any major-league orchestra which has recorded this music. In fact, I had just recently listened to the new Chandos recording of these two (orchestral) Symphonies from Andrew Davis and the BBC Philharmonic. I thought Davis’ way with Stravinsky is typical of him - warm, refined and musical - enhanced by plush recorded sound from Chandos. But he's not the most exciting conductor. Whereas I thought Dima to be more faithful to the composer - incisive, dynamic, energetic and more identifiably Russian. Listening to the 2 recordings back-to-back over several days, this impression persisted in Symphony In Three Movements, but not necessarily for Symphony in C, where I thought the tables were turned. Intrigued by the two approaches and how they succeeded differently in the two works, what started as a review of the BIS has evolved into a closer look at both discs. Moreover, comparing the two is logical, as they have much in common. Both are recent releases from two of the most esteemed Classical labels, and both are offered on SACD. And that last bit is important; for in the end, I found the recorded sound to be as much a factor as the conductors themselves. Right from the beginning of the opening movement of Symphony in Three Movements, I was taken aback by the incisive articulation from the Galicia strings - aided by the extraordinarily transparent BIS recording. Rarely have I heard such precision of execution and observance of the many accents and downbow markings - and especially the crisp marcato indications. The resultant bite and spikiness are most appropriate and wholly characteristic of Stravinsky. Textures are airy and transparent, revealing intriguing inner details which often go by unnoticed, and extraordinary clarity to the piano contribution. All combined, this reading exhibits the spirit and very essence of the piece. Comparing this to Andrew Davis in the same (1st) movement, yes Davis is a bit warmer and seemingly less incisive. But is he really? Actually I think it’s the Chandos recorded sound which makes it seem that way. I cannot fault the articulation of the strings and there is plenty of bite to brass. But Chandos softens it just slightly, capturing more of the plush, reverberant acoustic. And the overall effect becomes a bit more “symphonic”. I was much more energized by Dima's Galicia orchestra, which is more sparkling, detailed and expressive. Dima pulls ahead interpretively, too, in the remaining movements. The 2nd movement is positively delightful and full of charm; whereas Davis is a bit more earthbound and matter-of-fact. In addition, the transparent textures on BIS reveal more inner details as important contributions, allowing the music to positively dance. The atmospheric acoustic, too, is most alluring - shimmering with orchestral color. The differences are even more pronounced in the finale, where Davis is slower and more ponderous. Dima more closely follows Stravinsky’s con moto indication and propels the music with energy and charisma, bringing the piece to a thrilling conclusion. Symphony in C is similarly played by both orchestras, however the extra richness of the BBC Philharmonic pays dividends. And Chandos provides better recorded sound here than in the other symphony on the disc. The booklet reveals it was recorded 3 years earlier (in 2019) and we can hear more spaciousness to the acoustic. And Davis has real vision in this work, especially in the first movement, where in the climactic section (about 5 minutes in) he generates majesty and sweep as the violins soar in their upper registers with ardor and a glorious body of tone, surrounded by air. The scope of this movement is most impressive. Meanwhile, Dima’s crisp, precise approach emphasizes expressiveness and characterization. Both readings are most enjoyable, but Davis brings that extra bit of grandeur which is wholly appropriate. In the 3rd movement, Davis is more characterful and dynamic - helped by the excellence of the Chandos recording. However, he is unusually slow and plodding in the opening of the finale, before lightening the mood delightfully in the tempo giusto which follows. Dima is less grandiose at the beginning, and then takes off at a very fast clip, leaving his strings scrambling to keep up with him as the movement takes flight. But there’s no denying his enthusiasm. The improved sound Chandos provides for Davis in Symphony in C elevates it to a higher level of musical involvement. Similarly, it must be emphasized how important the superb BIS sound is to the success of the recordings in Galicia. The orchestra is presented with immediacy and clarity in a well-defined, spacious acoustic - yet with more warmth, color and richness than is often heard from this label. This is simply wonderful recorded sound - one of the very best I’ve yet heard from BIS. Choosing between these two releases is difficult and I wouldn’t want to be without either. Both are excellent, but in slightly different ways, as expected. Dima is fleet, incisive and expressive; Davis is warmer and more symphonic. That’s the quick and easy summary. However, couplings may be a deciding factor for some. Davis plays a somewhat tepid and under-characterized Divertimento from The Fairy’s Kiss. While Dima, perhaps more appropriately, plays a splendid Symphonies of Wind Instruments (in the original 1920 version), bringing similar incisiveness and expressiveness as heard in the rest of the program. And his winds exhibit a beautifully refined sound which is most appealing. I strongly prefer this over the Chandos coupling. Dima Slobodeniouk has a real feel for Stravinsky. And with such an intimate, deeply developed relationship with the Galicia orchestra, they respond with involvement, vigor and commitment. It was a real pleasure hearing them play this music so expertly. This BIS release is quite simply outstanding. Oh…there’s one more interesting aspect which these two releases have in common. Both are comprised of recordings separated by several years - 2019-2023 (BIS) and 2019-2022 (Chandos) - presumably necessitated by the Covid-19 pandemic. We should be ever grateful these dedicated, committed record labels did not abandon these projects. Both were well worth the wait.

0 Comments

This may sound like a strange observation, but for me, one of the stars of this show, aside from the composer and the conductor, is the orchestra "leader" (or as non-British orchestras call them, the concertmaster).

Anyone who follows my blog will have undoubtedly read my extreme irritation with this orchestra's string section on their most recent album of music for strings - where their manic, frenzied vibrato was just ridiculous (especially in the Enescu). The "leader" on that album was Charlie Lovell-Jones, and I suspect he is largely responsible for the string sound heard there (though likely coaxed on by the conductor). I was thrilled to hear the orchestra's strings return to normalcy and good taste on this new album of music by Kenneth Fuchs (just as they had been on Volume One in the series). And noting this is a different "leader" seems to confirm my suspicions. The leader for this recording session is John Mills, just as he was on the previous Fuchs album. And the strings are positively glamorous - shimmering, vibrant, silky and lush. Nowhere to be heard is the frantic, hysterical vibrato we heard from this group on the Music for Strings album. One wonders why John Wilson allows it to occur with one "leader" but not the other. That being said, I found the orchestral playing on this new album to be absolutely sensational. Moreover, recording engineer Ralph Couzens has once again found the optimal positioning for his microphones (after the mishap with the Daphnis and Chloe recording). The orchestra has regained clarity and focus within a spacious acoustic, and dynamics expand effortlessly and powerfully into the hall. All I can say is - hooray for small miracles! Now getting to the matter at hand, I was a little disappointed to discover there isn't a whole lot of new music on this second volume of orchestral music by Kenneth Fuchs. Of the four pieces recorded here, three are re-orchestrations of preexisting works and only one is newly composed. Fortunately, the reworked material is quite rewarding. Eventide was originally written for English Horn and Orchestra, as recorded by JoAnn Falletta and the LSO for Naxos in 2003. It is played here by an alto saxophone instead. The bass trombone concerto was originally written for a wind band accompaniment, while the "Point of Tranquility" was an original concert band work. Both have been previously recorded in their original band versions but are transcribed for orchestra on this new recording. Only the opening work, Light Year, is completely new. I don't mean to sound disparaging. All of this music is quite wonderful (though not quite as wonderful as that on the first volume) and certainly benefits from the boundless color, dynamic range and atmosphere only an orchestra can produce. And with John Wilson on the podium (and John Mills leading the violins), and the very best recorded sound from Chandos - well it doesn't get much better than this. I'll save the new work for last (and indeed I listened to it last), so let's start with the glorious saxophone playing of Timothy McAllister in Eventide. I wasn't expecting to enjoy this as much as the original, but I did. With a saxophone as soloist, the piece frequently reminded me of Henri Tomasi's magnificent Saxophone Concerto - one of his most accomplished works, and surely my very favorite piece ever written for saxophone and orchestra. McAllister plays with exquisite tone, not at all brassy or coarse. This is a sweet, buttery sound, infused with vibrancy and air (but not breathiness). And his vibrato simply shimmers with elegance, not unlike an English horn. However, there is an appealing bit of huskiness to it, along with delicacy. There’s also just the occasional hint of a jazz-influenced lip slur - but only rarely and just barely perceptible in its subtlety. In short, this is musicianship of exquisite eloquence - appropriate for the piece. Well, except for that strange 6th Variation ("Bong like a church bell"), where the soloist plays with a weird guttural flutter tone for no apparent musical reason. I couldn't remember the English horn playing it this way on the Naxos recording, but a quick spot-check confirmed it did - sounding even worse there. It sounds like McAllister is doing his utmost to minimize it as much as possible on his sax, but I simply don’t understand why it's there at all. Why disrupt such gorgeousness with this? Fortunately it doesn’t last long and mercifully does not recur. And it is immediately followed by the most luscious, shimmering strings you’ll ever hear on record in the next Variation. So all is good and my admiration for this version of the piece is restored. A bass trombone concerto is certainly not something I would normally be drawn to, but this is by Kenneth Fuchs so it just might be good! Not unlike his 2015 Glacier for electric guitar and orchestra, it’s the orchestral contribution which makes the piece interesting. It’s scored with all the color and resourcefulness an orchestra can generate, with the soloist almost an afterthought. The trombone part is not really all that interesting (maybe more so for trombone players) but manages to integrate itself into the orchestral fabric without being too conspicuous. James Buckle is obviously an excellent soloist, and I especially admired his lowest notes, which are played with exceptional focus, articulation and roundness of tone. The piece is laid out in 4 continuous sections lasting 14 minutes, which is more than long enough. The orchestration of Point of Tranquility brings about a complete transformation from its original band version. I don’t know if it was a lackluster U.S. Coast Guard Band, or an uninspired director, but I found the piece rather pointless (excuse the pun) on their 2018 Naxos recording of the original. In this orchestral version, it's just as colorful and atmospheric as other orchestral works by Fuchs. There are beautiful solo passages (the opening trumpet, as joined by some woodwinds, exhibits a luscious blend of sound), followed by big swashes of orchestral color, surrounded by arpeggiated filigree played by all manner of instruments - harps, bells, clarinets (and maybe 2nds and violas). But this isn’t the brilliant splashes of color like we heard in Cloud Slant on the earlier album. True to the title, this is even more relaxing, almost meditative, like soft waves washing onto the sand. And at the end, I concluded the music really did portray tranquility - in a way a military band couldn't possibly. The piece is a complete success in this orchestral revision. It's like going from black-and-white to color. Or even more pertinent - mono to stereo. Even though it isn’t newly composed, it sounds newly minted as played by John Wilson and this fabulous orchestra. Finally, the all new work, Light Year (suite for orchestra) is unmistakably Fuchs, and can be by no one else. But it’s not quite as uniquely original as I was hoping. It’s very similar to both Tranquility and Cloud Slant. It seems to combine all the atmosphere of the former with all the color and vitality of the latter in its portrayal of the universe - from the nothingness of space in the opening section, to the brilliant splashes of light which ensue. The endless arpeggiated undulation, agitated and swirling strings, bubbling swashes of color, and sudden brassy outbursts are all instantly recognizable from Fuchs’ other works. Don’t for a minute compare this with that familiar suite of planets; no, this is absolutely nothing like that. It’s more ethereal, more cosmic, and certainly more glittering. This music is more about atmosphere and imagination than compositional substance. In fact, I thought it perhaps went on a bit too long without developing real thematic material - or even a memorable tune (though the wistful melodic line on the violins, later echoed by the horn, in Lunar Valley is enchanting.) Even the Scherzos are propelled primarily by bustling, scurrying string flurries. There are certainly lots of notes in this piece! Not to say I didn’t enjoy every minute of it. I certainly did. But remembering my earlier observation about the importance of the leader of this orchestra, this piece demonstrates why. It’s an orchestral extravaganza - a display of extreme virtuosity and bravura requiring the ultimate in color, panache and finesse. It exhibits masterful orchestration, at which Fuchs is brilliant. As I noted in my review of his music on the first volume, Fuchs can make almost anything - or almost nothing - interesting just with his extraordinary orchestration. And that's what I admire most about it. This is orchestral playing of the very highest distinction - with positively ravishing string sound throughout, thanks to Mr. Mills. After a second listen, I began to more fully appreciate everything this piece has to offer, and realize I may have underestimated its creative distinction. In fact, I consider this to be Fuchs' Concerto for Orchestra - more so than Cloud Slant, which the composer himself subtitled "concerto for orchestra". Light Year features dazzling displays from every section of the orchestra in succession - strings here, brass there, and percussion definitely in Hot Ice, where along with bravado trombone glissandos and bold brass interjections, I was reminded of rousing movie music (specifically John Williams and Star Wars). The finale launches us into the cosmos with a splendid orchestral spectacle before fading away into the farthest reaches of outer space - bringing the piece to a wondrous conclusion. And it most definitely should have come last on the program. But that’s just me. In sum, I’m happy to hear the Sinfonia of London sounding glorious again. We can hope Mr. Wilson understands that we can hear the difference. I’m also happy that Chandos has once again achieved superlative recorded sound. We can hear the difference with this as well. And these things matter. Finally, I look forward to more new music from Kenneth Fuchs, hopefully on a future installment with John Wilson - and with John Mills in charge of the strings. A fantastic debut album from the fantastic Pacific Quintet. Unity themed, it combines composers from 6 different nationalities, 5 of which correspond to the home countries of the players (Bernstein being the “extra”). The booklet is skimpy with details (about the music and the musicians) but a quick Google search reveals this is a Berlin-based group. And while the nationalities represented by the players are listed on the back cover, they are not directly correlated with the individual musicians for some reason.

But grumbles aside, the music is interesting and varied, and the playing and recorded sound are absolutely spectacular. Fazil Say (Turkey) is a composer I appreciate more and more with my every encounter with his music. He’s a seriously good piano player too, but so eccentric and flamboyant at the keyboard (with ridiculous vocalizations while he plays), I don’t collect many of his recordings. But he’s a truly gifted and imaginative composer and this opening work fully demonstrates it. As to these compositions from 6 different countries, the booklet continues to frustrate with its lack of useful information. There are no translations of titles or movement labels anywhere to be found. Google can assist in some instances, but I couldn’t get it to identify any of the Japanese or Turkish words. Thus I have no idea what the title of Say's work means. Relying only on the brief summary provided in the booklet, we're told it depicts a day in the life of 5 old Turkish men. Interestingly, the piece has only 4 movements, so I’m still a bit puzzled by what’s going on. So I will concentrate solely on the music itself - and this piece is an absolute knockout! And the perfect concert opener to showcase the capabilities of this group. It is highly virtuosic and expertly scored for this specific combination of instruments. And indeed, the playing is simply amazing (and I don’t use that word often). The music sounds to be incredibly difficult to play - including rapid, repeated articulation (staccato double-tonguing), dizzying trills, sharp stabbing low notes from the bassoon and horn - all made to sound absolutely effortless in their execution of it. In addition, there is gorgeous tone - colorful and expressive - from all 5 players, along with an extraordinary dynamic range. And I’m hearing all of this just in the opening fantastic presto! All of these characteristics extend into the Moderato, while the Andantino calls for expressive lyricism, where we hear gorgeous, vibrant flute tone and a robust, golden-hued horn (which never overpowers the others). The closing Presto returns us to the extreme bravura of the opening movement, beginning with incredible pianissimo filigree alternating between the flute and clarinet - again sounding completely effortless, yet menacing at the same time. And later on, incredibly the same gossamer flourishes are assigned to the bassoon and horn, back and forth, played just as effortlessly. I have to admit I was astounded by what I heard. Not only the music, but especially by the playing. The remainder of the program never quite rose to this exalted level of compositional or musical achievement. However, there is a lot of interesting and rewarding music. Especially Vida by Jorge Santos (Honduras). After a rather strange introduction, it is followed by 6 short, characterful sections which depict “human life in 10 minutes”. Each is descriptive of its given subtitle (as translated by Google): curiosity, imagination, puppets, wandering, “busqueda” (searching, I believe?), and fullness (of life?). The music is endlessly varied and interesting, and I found the work captivating and over much too soon. The “Medley of Japanese Folk Songs” by Kyousei Yamamoto (Japan) is another delightful work, obviously based on folk songs. Its 4 movements are very short and to the point: 1) a jig-like dance; 2) a song; 3) playful - charming and delightful; and 4) songful and reflective. I found it very entertaining, and like Vida, simply too short. I wanted more from both of these wonderful composers! Now things get a little more serious with the Divertimento for woodwind quintet by Hanns Eisler (Germany). This was composed 20 years before his more familiar Nonetto #2, and 90-100 years before almost everything else on this CD. And yet it sounds by far the most “modern”. This was written during his 12-tone phase while a student of Arnold Schoenberg - and it sounds like it. Fortunately he grew out of it quickly and eventually began composing film music, during which time he wrote his two Nonettos, which are decidedly more melodious and tuneful. This Divertimento is not nearly as appealing, but agreeable enough if you like Schoenberg. Jumping ahead exactly 100 years, musical satisfaction improves with the Three Bagatelles by Soeui Lee (South Korea). Each is delightfully contrasting, beginning with some charming music for a marching band. It incorporates some unusual techniques such as subtle flutter-tonguing, and features the horn prominently. And what a fabulous player Haeree Yoo is! This is followed by a lyrical Serenade propelled forward by a delightfully bouncing bassoon. And the piece concludes with a Korean Dance, featuring traditional Korean rhythms. If not quite as musically rewarding as the first three works on the program, it is nonetheless enjoyable and over too quickly. To close the concert, I was disheartened the group chose to represent the United States with yet another frivolous, superfluous arrangement of 3 hit tunes from Bernstein’s West Side Story. If the U.S. had to be represented at all, why not choose another original work for woodwind quintet? After a program of fascinating, wonderful original works for woodwind quintet, I wasn’t at all interested in hearing them play a merry arrangement of I Feel Pretty. I’m sure it provides a stirring encore for those who are so inclined to listen to it, which I was not. The production itself is very fine, including charming pictures of the musicians on an attractive trifold cardboard enclosure. The rather inadequate booklet, though, is disappointing. I would have expected to read something - at least a brief bio - about this ensemble on this, its debut album. And given most of the program is comprised of new music from composers likely unknown to most of us, I expected more thorough program notes too. I did read on the back cover that 2 of the works were commissioned for this album and we can presume these are premier recordings. Fortunately, the recorded sound is superb and the playing of this group is jaw-droppingly awesome. I love a highly accomplished woodwind quintet, especially as there is so much really good music written for the genre. Several outstanding groups have released CDs recently which I have enjoyed enormously - including the Monet Quintett (on Avi/SWR2), Orsino Ensemble (Chandos), and members of Ensemble Arabesques (Farao Classics). The Pacific Quintet can certainly stand proudly among them as one of the very finest. I simply cannot wait for another album from them - or from any of these other groups as well. I have enjoyed many CDs over the years from the Belgian chamber ensemble, Oxalys. On the Fuga Libera label, the Mozart and Ries Flute Quartets are simply glorious. And more recently on Passacaille, entire albums of marvelous chamber music by Jean Cras and Joseph Jongen are real finds.

Oxalys began producing their own recordings on the Passacaille label about 10 years ago, and along with new projects, reissued some of their previous out-of-print titles as well. Their two newest recordings reveal something of an evolution of the group - not only in overall sound, but also in expanding their instrumentation to explore a wider range of repertoire. The 2021 CD “Nonetto” brought about a notable transformation in the group’s recorded sound, which is now slightly more forward and immediate than the more atmospheric glowing blend heard on previous recordings. There is a more detailed individuality afforded each member of the group - as if going from sitting down to standing up and playing in a more soloistic manner. Nino Rota’s Nonetto is an example of their somewhat more upfront and incisive sound. While there’s no denying the invigorating enthusiasm in the playing, I do miss a bit of warmth - especially when compared to Eric Le Sage’s wonderful collection of Rota's chamber music on Alpha Classics, which is slightly warmer and more colorful. Both recordings are excellent, though, and choosing one over the other as a primary recommendation would be impossible. Hanns Eisler’s Nonet #2, which comes next on the Oxalys program, is then a touch more relaxed and atmospheric - wholly beneficial and appropriate for the work. This is highly descriptive music, composed during the time Eisler was writing film music. (His first Nonet was actually written as film music.) The playing is full of charm and character, made even more so by its tasteful inclusion of percussion (delightful xylophone interjections here and there bring smiles every time). This piece is wonderfully creative and appealing and would, in fact, make splendid ballet music. In the final Nonet (#2) by Martinu, Oxalys successfully combines the color of the Eisler with the energy of the Rota in a winning performance - though I have heard it played with just a bit more charm and wit than it is here. It is nevertheless enjoyable and brings the concert to a splendid close. Their newest (2024) release, “The American Album”, begins with Copland’s Appalachian Spring ballet in its original version for 13 instruments. And it is one of the most convincing performances of it I can remember hearing. Indeed, for the first time, I began to appreciate it much more than the ever-popular orchestral version. Its intimacy and more transparent scoring evokes a completely different emotional reaction which I found most attractive. But again, this is a more direct and detailed interpretation of the piece than often heard, which perhaps could use just a touch more love. It is expressive certainly (and beautifully played), but not overly contemplative. However, it is afforded superb recorded sound which presents the group with presence and realism in a lovely, spacious acoustic. This performance is most appealing, if in a rather no-nonsense rendering. John Adams’ famous Shaker Loops is also played in its original setting for 3 violins, viola, 2 cellos and a bass - but in its alternate “through-composed” version rather than the “modular” one which invites the musicians to “independently intervene” during the performance. (I’m not sure exactly what that means and don’t think I’ve ever heard it played that way.) Oxalys plays it with extraordinary precision, and the recording is highly detailed, revealing every inner strand. The first movement is incisively articulate with vigorous propulsion. The 2nd, in stark contrast, is surreal and unexpectedly mellifluous, as the players breathe exquisite tenderness into all those little glissandos. The 3rd movement starts similarly - lyrical, almost lovely, yet kept marvelously simple - before an underlying rhythmic insistence asserts itself. The music builds to an incredible, sustained climax (magnificently projected by the recording) - like an unstoppable locomotive approaching at full steam - before it finally releases the delirious intensity, dissipating into ethereal harmonics. The finale once again takes up the incessant rhythmic pulse - mesmerizing in its nervous restlessness - demonstrating minimalism at its absolute finest and most effective. I've never been so thoroughly immersed into this piece as I was listening to this recording of it. The playing and recorded sound are electrifying - keeping the listener transfixed from beginning to end. The closing Meeelaan by Wynton Marsalis then is quite unusual - made even more so with its unusual scoring for bassoon and string quartet. The music itself is creative and certainly entertaining, but I wasn’t sure that a bassoon was the appropriate choice of soloist for music with movements titled “Blues”, “Tango” and “Bebop” - with a cadenza thrown in for good measure. (I read in the booklet this piece was originally a commission in 1961 for a bassoonist, which explains the instrumentation.) The playing is characterful and thoroughly idiomatic, but hearing the bassoon in these styles just wasn’t really convincing musically. The final Bebop, curiously, was the best, where somehow the bassoon and strings are great partners. The music is so good, I almost wish Marsalis would rescore it for a different instrumental soloist. Both of these new albums offer adventurous programs - expertly played and recorded in clear, detailed, articulate sound. Moreover, the Passacaille productions are first-rate - including informative program notes, complete recording details, and imaginative, positively irresistible cover art. Highly recommended. One wonders why.

Why record more Mozart symphonies? What’s special about these that merits a recording of them? BIS is apparently embarking on a complete cycle with clarinet player-turned conductor Michael Collins and the Philharmonia Orchestra. So let’s give this a listen and see what's special about Michael Collins on the podium. Focusing on the outer movements, these readings are certainly vigorous but not necessarily invigorating. They sound rather driven and lacking in charm and finesse. And BIS emphasizes this impression with boisterous recorded sound, slimming down the Philharmonia's usual body of tone. This sounds more like a chamber orchestra to me; indeed one would never guess this is the Philharmonia Orchestra. I find this odd. This is one of the best orchestras in the world which could never possibly be described as sounding “thin”. So why do they sound that way here? I perceive a sufficient number of strings, and Collins mercifully does not insist they play with any suggestion of “period performance” techniques. Thus the strings (and woodwinds) play with vibrato. But I miss warmth. Tempos are very swift (which under normal circumstances would be a good thing) but there isn’t a joyful impetus to them. Speeds are fast merely because the conductor is beating time that way. However, the inner movements fare better. Collins relaxes his grip on the rigid tempos, allowing various solos and instrumental choirs time to shape musical phrases. The playing gains expressiveness, though I still miss a sense of singing lines. For even here, there is a matter-of-fact directness which merely gets to the point and moves on to the next bustling Allegro. As a whole, I would describe Collins' way with these symphonies as determined rather than inspired. This is crisp, vigorous, no-nonsense Mozart which is rather lacking in sheer joy. The Philharmonia dutifully plays all the notes with expert precision at the speeds in which they are led, but the orchestra lacks much of the warmth and color we expect from them. The stunning immediacy of the recorded sound tends to exacerbate this effect, highlighting the whiplash dynamics and hard banging timpani - emphasizing the noisy, busyness of the scores. Whether this is all Collins' doing, or the BIS engineers, or the slightly dry hall acoustic - I cannot say. I suspect it's a concerted combination of all three. In a very crowded field, I was attracted to this new recording because it is played by the Philharmonia Orchestra. But this isn't big-band Mozart. It sounds more like a chamber orchestra, which is not necessarily what I was looking forward to hearing. But as such, it is effective enough. It will be interesting to hear what unfolds in the next installment. I’ve been disappointed with Pentatone lately - for good reason. (Please see my blog for reviews.) However, this latest release is a bit different. And a lot better than what I’ve been hearing from the label so far this year. For two primary reasons: 1) It’s the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, which is in superb form these days; and 2) it’s conducted by Stephane Deneve, who is a superb conductor and always impresses me with his every recording.

Right from the first Allegro, one immediately recognizes the orchestra is engaged, enthusiastic and dynamic - which is an enormous improvement over the disinterested San Francisco Symphony in Pentatone's recent release of the Bartok Piano Concertos. And Deneve imbues these two pieces with vitality, musical insight and a real understanding of the very essence of the music. They come alive as never before. And then there’s James Ehnes. I love his rich, resonant, wooden tone (not as husky as Zukerman's, but in the same ballpark). But let’s be honest, he’s not the most exciting player. He can be a little sleepy on record. But not here. Deneve takes charge of the proceedings, commands the attention of everyone involved, and encourages real spirit in his playing. (Just as he did with the Jussen brothers in their 2017 recording of the Poulenc Double Concerto on DG). Simply put, these performances of both works are inspiring and full of life. Moreover, they display a stimulating sense of new discovery. And that’s actually quite an achievement, because both of these pieces are a little reserved rather than outwardly flashy. Consequently, the Bernstein isn’t all that frequently recorded (though two excellent ones come immediately to mind - Gluzman and Neschling on BIS [2009] and Brian Lewis and Hugh Wolff on Delos [2006]), and this is only the second recording of the Williams concerto (in its revised, present form). So a fresh new recording of both is most welcome. Bernstein’s Serenade has always struck me as an unusual piece. It can seem a bit too serious for a serenade; and featuring a solo violin, it's not a full-scale violin concerto either. But it is so characterful, delightful and full of vitality as played here, it succeeds at being both. Ehnes is the perfect violinist in the opening Lento - his tone sweet and rich at the same time, beautifully singing in the aching, soaring melodic lines. The Allegro marcato then instantly springs to life, as the orchestra (scored for strings and percussion only) asserts itself with authority, with the violin dancing around them delightfully. This continues into the Allegretto before the capricious Presto takes off on an exciting, almost breathless jaunt - marked by perky spiccato. A lengthy Adagio leads into an even lengthier finale, which begins very severely, but soon erupts into a drunken discourse with unmistakable, jazzy influences reminiscent of Bernstein’s music for the film On the Waterfront - written the same year (1954). And the molto vivace final section brings the piece to a rousing conclusion. Deneve infuses each movement with a thoroughly idiomatic, traditionally American flavor which is unmistakably Leonard Bernstein. I’ve never heard the piece sound so delightful, or all that exciting. Or, for that matter, not even all that distinctively “Bernstein”. But all that changes in this performance. It is so full of fervent melodies and infectious, jazzy dance rhythms, Bernstein's unique character shines through, revealing this to be one his finer symphonic creations. And with James Ehnes as a spirited soloist - well, this is a real surprise. John Williams' (1st) Violin Concerto, written 20 years later (coincidentally premiered by the St. Louis Symphony), is a fine piece too - at least in this recording of it. I thought it was a bit reticent in Gil Shaham’s 2001 DG recording of the 1998 revised version, and I was never completely convinced or overly impressed with it. But in this new reading, it is full of an impassioned, emotional outpouring of rhapsodic singing lines and rich harmonies which was somewhat curtailed in the earlier reading - perhaps in an effort to make it a more "important", “serious” work rather than just a trifle from a “film composer". And again, just as in the Bernstein, James Ehnes is perfect in the opening Moderato - resplendent in the singing lines. It is a bit too long for sure, especially as it is followed by a similar, slow-moving central movement, where Ehnes' sweetness of tone is exquisite in a peaceful, contemplative way (as indicated in the score). In the final movement, which at last provides some much needed liveliness, Deneve unabashedly brings out the unmistakable John Williams element in the opening, with chimes and percussion announcing its arrival, and later with golden, chordal brass. That may sound like a strange observation, but the piece really doesn’t sound much like John Williams (at least not the John Williams of E.T.) - until here. I have always thought John Williams tries too determinedly to NOT sound like himself in his non-film scores, so it is refreshing to hear a bit of the John Williams we know and love in his violin concerto. The piece is still rather unassuming, and really could use a Scherzo in between the two slow opening movements. But it is so much more engaging and coherent in this new recording, it gains in significance and becomes more musically satisfying. It is certainly infinitely more interesting and musically substantive than Williams’ dismal 2nd Concerto written for Anne-Sophie Mutter in 2022, whose recording of it on DG is truly abysmal. This Pentatone release is a bit of a melange. According to the booklet, the two pieces were recorded 4 years apart, each with a different recording production. The Bernstein was recorded in November, 2019 by the St. Louis Symphony team, and the Williams in January, 2023 by Pentatone. Remarkably, the recorded sound is excellent on both occasions. Why they are just now appearing (together) on this CD is a bit of a mystery, but in the end it doesn’t matter. Both pieces are superbly played and they make perfect discmates. I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this nearly as much as I did. It is a wonderful recording in every way and a very pleasant surprise. The Miro Quartet has been around since 1995, and astonishingly, 3 out of 4 of their long-standing members (since 1997) are still part of the group today. (The current 2nd violinist joined them in 2011). They haven't made many recordings over the years, but two are exceptional. Their 2003 recording of George Crumb’s Black Angels (part of the “Complete George Crumb Edition” on Bridge Records) is surely the most successful CD version - musically and technically - I have heard. It is simply awesome. And so is their complete set of Beethoven quartets, recorded over a 15-year period (2004-2019) - compiled by Pentatone from various sources and reissued in a terrific box set on their own label in 2019.

This new disc is, curiously, a local radio production (recorded at an Austin classical radio station) which Pentatone is distributing on CD with their logo (similar to their recent Bartok Piano Concertos CD which was recorded by the local San Francisco Symphony team). It is an innovative and attractive program featuring two commissions - from Kevin Puts and Caroline Shaw. The Puts work, “Home”, is cast in 3 continuous sections, the first of which is melancholy and full of anguish - made more so by the frequent use of rolled quadruple-stopped chords, exaggerated for maximum dramatic and emotional effect. The 2nd section lightens instantly, glistening with harmonic motifs over rugged rhythmic pulses. The music becomes quite dissonant along the way (perhaps a little too deliberately) before leading into the final section, marked “dangerously fast”. This is rather more minimalistic in origin - attractively so - but doesn’t sound especially “dangerous” or even all that fast. However, it establishes a more unique voice, including some wild glissandos and intense ¼-tone outbursts, which is quite engaging. There are some achingly expressive passages in the violins too, and the piece closes with some more elongated, multi-stopped chordal sighs similar to those heard in the first movement. This is an effective and interesting piece, if ultimately not really memorable. A bigger disappointment comes with the new Caroline Shaw work, whose music typically brings something fresh and novel. But here we're confronted with spoken dialogue in the form of poems recited by an anonymous female voice (unidentified anywhere in the production) before each section of music (7 in all). I personally never like spoken word as part of a music program in any circumstance, but it is especially intrusive and annoying here because nothing prepares you for it. No "narrator" is named in the credits, and nowhere is it revealed that recited poems are a part of the piece. (Even the program notes are vague about it.) Worst of all, they are not individually tracked, so it's impossible to skip over them and just get to the music. The poem readings are mercifully short (and so are the bits of music which follow them) but made even more annoying as spoken in a florid, up-close sotto voce. Unfortunately, the music itself isn't all that interesting. It’s not as creative or imaginative as we have come to expect from Shaw. Oh, she employs all the identifying characteristics from her usual bag of tricks - bow scratchings, portamentos, quarter-tones, tonal harmonies coming out of noisy effects, etc. - so we definitely know it’s her. But there just isn’t much musical substance to it. I found it interesting reading the Miro Quartet’s comments in the booklet that they had Zoom meetings with the composer during which they made "suggestions" - and at one point had to ask her to take out her violin and demonstrate for them some “unique string technique” she specifies in the score so they could understand what it was she was asking for. At some point, enough is enough with it. Just write good music. The most satisfying piece on the program is surely George Walker's Adagio from his 1st String Quartet (more familiarly known as Lyric for Strings in its version for string orchestra). It is beautifully played here, and how I wish they had played the entire quartet rather than Barber’s. The catalog could really use a new recording of the complete work. The Miro Quartet's reading of the Barber Quartet is a chore - certainly not one I will ever return to again. I found it a little detached and uninvolving (where is the fervor in the opening appassionato?), burdened with slowish tempos in all three movements - extraordinarily so in the famous Adagio, which has so little forward momentum it hardly has a pulse. And when the big climax finally arrives, we hear some rather strange melodramatic, emotive, accented impulses which just don't sound right. To illustrate just how seriously slow this Adagio is, the Miros take almost 3 minutes longer (!) than the Emersons (DG) and Yings (Sono Luminus), and well over a minute longer than the very leisurely Escher Quartet on BIS. Coming after the Molto Allegro/Presto conclusion of the Barber (which isn't molto or presto), the program inexplicably ends with an arrangement of “Over the Rainbow” for no conceivable or musically justifiable reason. Why they put it there is beyond comprehension. It is a lovely thing - exquisitely intimate and lovingly played - but so absurdly out of place here at the end of the concert. Pentatone has long since abandoned their dedication to state-of-the-art DSD/SACD recorded sound (which is what put them on the map in the first place), and this release is a standard stereo CD which isn't even recorded by them. Considering the source, the sound is quite good - though I thought the group sounded a bit “confined” at times, and the acoustic could become a bit congested and dense in the more intense moments. A little more air and spaciousness would have been beneficial. Pentatone continues in strange directions, as evidenced by many of their recent releases. This one had potential - accomplished playing, some interesting music and attractive cover art. But with all the misgivings noted above, it is far from satisfactory. I had high hopes for this release. I love these 3 masterpieces from Dutilleux‘s first creative period, and to have them all on one CD (over 78 minutes of music) is very enticing. They are imaginatively scored with ingenious orchestral effects (especially in the strings), exploiting all the color and atmosphere available from every section of the orchestra. And the results can be mesmerizing.

But not in Gimeno’s hands. In general, he favors emboldened details and calculated perfection over atmosphere and color. He dissects the score, bringing every detail forward for no apparent musical reason. This approach renders the First Symphony pedestrian and uninteresting. Even the molto vivace Scherzo is steadfastly earthbound. Metaboles is seriously undermined by a lack of atmosphere. The orchestra sounds too loud most of the time (and too close), with precious little truly soft playing, leaving crescendos nowhere to go. Dynamics seem confined to a casual mp-f range. Details are clearly audible, but they’re just details without context. There is no mystery or intrigue or allure. Instead of experiencing something which captures the attention, making one wonder, “what was that?”, or “how did they make that sound?”, we hear beating percussion, staccato flutes and piccolos, and col legno and harmonics in the strings - which are merely soundeffects. It doesn't create an otherworldly soundscape; it’s just…there. Gimeno tells you what he wants you to hear, rather than inviting the listener to experience it for themselves. To be fair, the recording does him no favors. The orchestra is clear and immediate, but lacks dimensionality - spread across the stage along a flat plane rather than layered back in expansive, gradated rows. The hall acoustic is minimalized, reducing blend, atmosphere and breadth. The cello concerto (Tout un Monde Lointain) comes off best. Soloist Jean-Guihen Queyras displays all the color, atmosphere and dynamic range Gimeno’s orchestra conspicuously lacks in the purely orchestral works. It is a captivating reading and Gimeno is actually a responsive accompanist. The recording perspective is a bit more spacious here as well, which is beneficial. After reading this concise review, I wondered if I’m being too critical. Maybe I’m getting used to Dutilleux's unique soundworld and am no longer as mystified or intrigued by his music. Not a chance. Pulling from my shelf the wondrous 2014 box set of his orchestral music played by the Seattle Symphony on their own label, conducted by Ludovic Morlot, I am instantly transported to another world. I find myself sitting in their hall, drenched in color and atmosphere and mystery - mesmerized by the glories of this music all over again. It is intoxicating, as if experiencing it for the very first time. And one can clearly observe superior orchestral response. Orchestral colors are vivid and richly hued, and dynamics are more pronounced and expansive, drawing the listener in with total immersion. The readings are simply more musically involving. The Scherzo in the symphony, for example, is far more exciting - especially after the indifferent Gimeno. And the outer movements are fleet, with momentum and real direction. And Metaboles glitters with color and atmosphere. Orchestral details, string effects and tingling percussion are now all part of the musical fabric, creating otherworldly atmospheres. The recording is more spacious and atmospheric as well. The orchestra is spread back 3-dimensionally in layer after layer, filling the hall, front to back and corner to corner. This affords a marvelous blend to their sound. And details become more musical - now part of the atmosphere rather than matter-of-fact. And the strings are lush and silky, shimmering in the acoustic, surrounded by air. (This Seattle set is a real treasure. Morlot was a worthy successor to Gerard Schwarz, and it's a shame they didn't renew his contract. He was perfect for them.) The Luxembourg Philharmonic is not at fault on this new recording with Gimeno. They play all the notes expertly and proficiently. But without inspiring leadership from the podium, they’re just notes. However, this would be a great recording to study the score to. You can hear everything in bold relief, scrutinized to perfection with laser precision. But without musical purpose, it just isn’t Dutilleux. I found it amusing reading harmonia mundi’s marketing blurb on the back cover which (accurately) describes Dutilleux’s musical universe as fascinating, mysterious, expressive and "…explores a thousand and one orchestral colours” - the very characteristics which seem to elude Gimeno. And they go on to claim "Gimeno...gives us flamboyant readings”. Not hardly. The recordings were made over a 4-year period - none of which is state-of-the-art. Despite meticulous playing, musically, this is a disappointing release. Here’s another sensational French string quartet that I’ve recently discovered, which instantly joins two of my other favorite French string quartets at or near the top of the list - Quatuor Hanson and Quatuor Diotima. Although Quatuor Arod has been around awhile (10 years or so), only the two violinists remain the same today. So while they’ve made a few recordings before, with and without new violist Tanguy Parisot, this is the first recording with all 4 of their current members, including the newest - cellist Jeremy Garbarg. Thus I would consider this to be from a “new” group. And "young" too; according to the booklet, they are all between 27-30 years old. So this should be an exciting release.

I wouldn’t normally be interested in a CD from the Warner label (er, should I say “Erato”, which is how Warner markets its Classical releases nowadays). However, occasionally they do offer something intriguing - which this one certainly is. To hear a “new”, "young", French string quartet playing Debussy and Ravel is enticing, but that they also include a world premier work commissioned by/for them makes it even more so. And that’s not all. What really makes this release special is the inclusion of an hour-long documentary film on DVD, which I found endlessly fascinating. (More on this anon.) The CD I listened to the CD before watching the DVD, and started with the new work, which was my initial attraction. And it doesn’t disappoint. Composer Benjamin Attahir explains in the booklet that Al Asr ("afternoon prayer") is one of the 5 elements of the Muslim salah. Musically, it is interesting, imaginative and expertly scored. And the superb playing of the Quatuor Arod makes it immediately impressive and engaging. The suddenness of dynamic extremes - always a hallmark of the very best quartets - is here in abundance, along with precision of articulation and variety and intensity of vibrato. This, combined with excellent recorded sound (yes - from Erato), is absolutely spectacular string quartet playing, and a gripping musical experience. The piece is cast in 5 continuous sections, with an interesting variety of emotional characterizations over persistent rhythmic underpinnings. It is somewhat tonal, but not tuneful. Specifically, there are occasional hints of melody over rhythmic pulses which sometimes bear tonality. The opening movement, Intense, is certainly that, while flavored with distinctive Middle East thematic motifs. This doesn’t sound like an “afternoon prayer” to me; it’s restless, anxious and nervous - brilliantly characterized by this quartet. Ancora is even more agitated and rhythmically insistent, while the Lontano is emotive and full of angst, including eerie harmonics playing brief snippets of melody. The Agitato 4th movement is very dramatic and rhythmically propulsive - just short of angry. It really gets the heart racing as tension builds with excitement. There are hints of Shostakovich too in an intense passage played by the violins in octaves. The dynamic extremes of this group’s playing are absolutely stunning in the dramatic outbursts in this section. And the music gets even more furioso in the final Fuga. The rhythmic drive is incredible, culminating in passages of real vehemence. But it’s not unrelenting. The momentum relaxes in the central section, creating an atmosphere of tension and almost unbearable anticipation of more to come. And when it does, starting with the viola, you should hear these guys dig in with ferocity to bow on string, accompanied with feral col legno as well. (And the 1st violin is practically screaming in a very Shostakovichian wailing passage up high.) This group isn’t afraid to get down with it and make some gritty, vociferous sound when called for. Yet it’s never ugly; it’s not even aggressive. It is at all times musically appropriate. But the sheer muscle and intensity in their bowing is extraordinary as they drive the piece home with dramatic propulsion. Surrounded by works of consummate refinement and mastery by Debussy and Ravel, I found it fascinating to hear this group play something completely different - bringing unbridled power and immersive commitment to this very contemporary work, combined with a frisson of new discovery. And what a discovery it is. This piece for string quartet is accomplished and imaginative, brought amazingly to life by these incredible musicians. I do wonder, though, why Attahir calls it “afternoon prayer” rather than something more pertinent to the driving rhythmic energy in it. Not for an instant did this music conjure up moments of prayerful reflection. But in the end, it doesn’t really matter; the piece is immensely engaging and appealing. I can’t help but think this should have come last on the program, though. How can Debussy or Ravel follow it? (It would be unthinkable in a concert setting.) So I decided to take a break and came back to the more familiar works on another day. My previous favorite new recording of the Debussy and Ravel Quartets was from the Quatuor Van Kuijk (yet another fabulous French group) on their 2017 Alpha Classics CD. I thought they were the freshest, most enlightening readings of these revered works I had heard. Well, the Quatuor Arod are even more illuminating - finding even more musical insights and variety of expression (especially in the Debussy), and play with such extraordinary freshness and spontaneity, it’s as if hearing this music for the first time. Listening to the Debussy, which comes first on the CD, all the qualities of the very best string quartets are immediately apparent, just as they were in the contemporary work. Unanimity of approach, wide dynamic range, natural musical expression, precision of execution, and uniformed interpretive vision. And above all, they sound positively orchestral in sound and scope. The first movement, in particular, is a revelation. There are many imaginative touches, revealing so many hidden musical details and nuances, I was reaching for my score as I discovered things I had somehow missed before. The second movement, in contrast, is distinctly articulate - with incisive bow on string and crisp pizzicatos. And it simply dances! It is so spontaneous and delightful, the music literally bubbles off the page as they playfully alternate musical phrases and punctuated pizzicato. The Adagio is heartfelt introspection with intimate singing lines, while the finale is captivating - brimming with all the qualities I’ve described above. And I must mention that the 1st violin's nearly-3-octave G-major scale in the final measures is surely the smoothest, most perfectly and effortlessly executed - while achieving a truly powerful, climactic fortissimo high B-natural at the end - I can ever recall hearing. This is certainly one of the most illuminating and rewarding recordings of the piece I have ever heard. They bring similar qualities to the Ravel, yet it is distinguished in a slightly different way. It is the group’s faithfulness to the score which is not only refreshing, but also enlightening. Ravel knew exactly what he was doing in his scores, and his string quartet is no different. He is very specific indicating what he wants, and thus his string quartet is perhaps slightly less amenable to interpretation than Debussy’s. And what impressed me most with the Quatuor Arod is their strict observance of dynamics and accents, and allowing Ravel's brilliant resourcefulness to shine through unadulterated. The opening Modere, marked tres doux ("very soft"), is certainly that - yet their tone is vibrant, even in passages played with only the slightest hint of vibrato. The Vif is delightful - pizzicatos contrasting with silvery, gossamer arco sections. And the Lent is heartfelt and contemplative, notable for some breathtaking pp and ppp playing. And then … the finale takes off like a jet, with enormous vigor and energy. Right from the very opening measures, there is a driving propulsion which is riveting. Listen to how they don’t make a slight hesitation before the 2nd and 4th bars like nearly every group does - presumably because it’s nearly impossible to play those double/triple-stopped fermata chords instantaneously after the 16th notes immediately preceding them. But these guys do it - effortlessly. Thereafter, the tempo itself isn’t hectic; nor is it driven too hard. Oh, it’s definitely fast - and very exciting - but there is weight and power behind it. Just listen to the muscle behind the bowing of the strongly emphasized accents, and the sheer force to the ferocious pizzicato quadruple stops in the 2nd violin and cello. Wow! And we haven’t even gotten past the first page yet! As the movement progresses, the group can instantaneously relax in the expressivo sections, beautifully and clearly differentiating between mp and mf. Again, it’s their adherence to the score which is most impressive - and musically significant. And the ending is simply exhilarating. I can’t conclude without pointing out the sensational playing of 1st violinist and founding member, Jordan Victoria. What an amazing player he is - not only the suddenness of dynamics, and the effortless, natural expression and lovely tone, but his ability to turn on a dime - from muscular, powerful “digging in” with the bow to a singing delicacy. I marveled at these characteristics in the Attahir as well, but they are especially notable here in Debussy. I also noticed several times throughout the program the rich, husky sound and gorgeous expressiveness of violist Tanguy Parisot as well. To say these readings of the Debussy and Ravel quartets are exceptional would be an understatement. They certainly can stand alongside those from the aforementioned Quatuor Van Kuijk as some of the very best I’ve heard. And in such a crowded marketplace, that is very high praise indeed. When one factors in the sensational new work commissioned just for them, this release becomes very desirable. And the accompanying DVD documentary is mere icing on the cake. The DVD I wouldn’t normally spend much time on a supplementary DVD, but this one is different. I was pleasantly surprised to discover this isn’t just a staged, “making of the CD” fluff piece. Rather, it is a legitimate, in-depth, feature-length documentary. (All the dialog is in French, with optional English subtitles.) The filmmaker follows the quartet in day-to-day activities, capturing them at length in rehearsals, on tour and in snippets of live concert performances. There are also extensive interviews with the individual musicians - especially with 1st violinist (and founder) Jordan Victoria, and to a lesser extent, the newest member, cellist Jeremy Garbarg. Not only does it document the group’s approach to making music, but also the individuals' involvement on a personal level. There are even a few historical clips of Victoria playing violin as a child; he was excellent even at the age of 8! The film begins with extended rehearsals/performance extracts of the group playing Bartok and Haydn (and short footage of a couple other works as well). And later on, there are extended rehearsals of the original group - with all 4 of its original members - playing Mendelssohn, which was enlightening. The film then recounts how the remaining 2 violinists found suitable replacements for the viola, and especially the cello, and how they learned to adjust to each other and open up to new ideas and candid criticisms from their new members. A lot of time is spent on the group being attuned to one another, musically and emotionally. And there is a lengthy segment on an obsession with playing in tune (which went on perhaps a bit too long). All these efforts can certainly be heard in their playing on this new CD. It is fascinating to observe them placing such an emphasis on absolute perfection, yet their music-making on the recording sounds remarkably spontaneous and utterly natural. The film’s final chapter captures an extended rehearsal session with the 95-year-old Hungarian composer Gyorgy Kurtag coaching them on his 12 Microludes. Victoria states the group had worked on the piece for months and thought they were well-prepared to play it, but Kurtag kept them for over 9 hours fine-tuning it. (In my opinion, though, no amount of "coaching" will elevate this piece to the level of creative mastery of, say, Bartok; or Ligeti and Penderecki circa 1960s; or even Kurtag’s own 1959 String Quartet, Opus 1.) What impressed me most was to witness what consummate musicians these young men are. They relished every moment they spent with the composer, eager to learn from him and try ever so patiently to understand the piece better. Maybe one day they’ll record it and we can judge for ourselves how it turned out. I was somewhat surprised the film spent so much time on the Kurtag session and none on the preparation of the new piece they commissioned for this recording. Not to diminish the Kurtag segment, but it would have been fascinating to observe their interaction with composer Benjamin Attahir as they learned and recorded his new work. Overall, I came away with a newfound understanding of - and appreciation for - what goes into making a group of 4 musicians into one of the very best string quartets (as opposed to one which is merely “very good”). The documentary reveals just how grueling it is to be a member of such a group (especially when on tour, spending days, sometimes weeks, together, practicing and rehearsing for countless hours), and what a personal dedication and commitment it is being a part of it all. I have to give Warner credit - this is a sensational release in every way. And it’s superbly recorded too, which I wasn’t expecting from “Erato”. What a pleasant and rewarding surprise. I recently wrote about Klaus Makela’s slick Debussy/Stravinsky Decca recording with the Orchestre de Paris, finding it superficial, completely devoid of character and interminably boring.

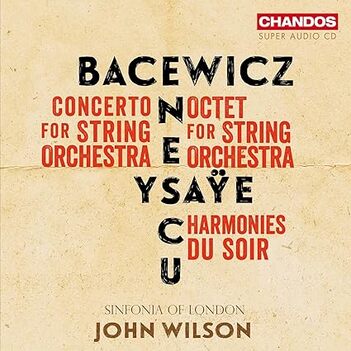

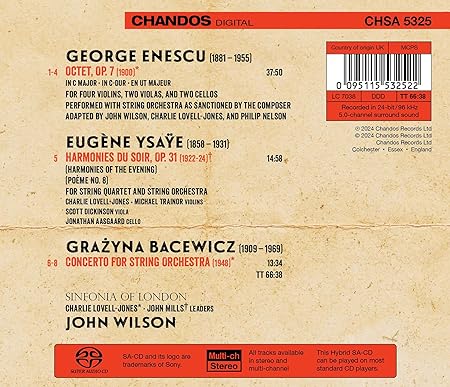

And then there’s this - whatever it is John Wilson is doing with his Sinfonia of London strings and that manic vibrato. Oh it’s definitely recognizable in a way Makela's is not (but not necessarily in a good way) and it's cropping up on his every new recording (definitely not in a good way). What I don’t understand is why his string section goes along with it and willingly does it for him. I would think the “leader” of this orchestra would put his foot down and put a stop to it. (Does he listen to these recordings? Doesn’t he hear how ridiculous that sounds?) But I have a theory on that (discussed below), and in the end, there can be no doubt this ultimately is all John Wilson’s doing. I admit I was almost dreading this release after what I heard in this team’s previous recording of the Berkeley Divertimento. (Please see my review here on the blog for details about it.) This program is so adventurous and enticing, I really wanted to like it. But I wasn’t looking forward to hearing what Wilson and his merry band were going to do to it. So I thought I’d start with Bacewicz’s terrific Concerto for String Orchestra (which is becoming quite popular lately), as I was sure it would keep the violins busy enough to not start in with that wild vibrato. I hesitantly pushed track 6 on the remote and sat back hoping it wouldn’t come. And it didn’t take long. Just 3:15 into the opening Allegro, as the melodic violin line begins to soar with increased intensity, they let loose with it. And boy-oh-boy do they ever. It’s that frenzied vibrato I heard in their earlier Berkeley. And now it can even be heard down in the violas (and maybe even the cellos?) too. UGH. Fortunately, it makes only a brief appearance before they all settle down and become a little less excitable and proceed with making music again. And make music they do in the Andante (which can be ravishing in the right hands). And, well, it is positively ravishing here. That mega-fast vibrato Wilson likes, when applied in moderation and with good taste, can be exquisitely shimmering. And here in the Andante, played con sordino, the string sound is truly lush. And a little later, Wilson takes his time in the calm, desolate interlude, allowing vibrant, singing viola and violin solos to emerge from the starkness of the atmosphere. Wilson is superb at this, and this was a truly memorable moment. The final Vivo then takes off with vigor, just as it should, and Wilson drives it pretty hard - barely letting up even for the Meno sections along the way. And mercifully, his violins are well-behaved. Comparing Wilson to Paavo Jarvi in his recent recording of the piece for Alpha Classics, I was surprised to hear more similarities than differences. And I suppose that is a testament to the accomplishment of Bacewicz’s writing and scoring. Sonically, Jarvi’s strings are just a bit thicker and bass-heavy, while Wilson’s are more textured and bathed in an almost too-warm acoustic. Musically, there are minor differences worth noting. For instance, Jarvi brings out the melodic lines more, giving them space to sing, while Wilson likes to bring everything out, whether important or not, creating a busyness underlying it all. Jarvi’s strings are not quite as luscious in the Andante, but he relaxes beautifully in the Meno sections of the finale, slowing noticeably more than Wilson does, creating more variety and illuminating wonderful contrasts. Both men bring enormous gusto to the conclusion - Jarvi’s bowing a little more incisive, and Wilson’s just a bit heavier on the string. Wilson tends to sound a touch more driven, as is his usual style. In the end, it would be difficult to choose between the two. Both are outstanding and receive excellent recorded sound. Since I started with the last piece on the disc, I decided to work my way backwards and listen to the Ysaye Harmonies of the Evening next. It is scored for string quartet and string orchestra, which I feared might get a bit thick with all the dense string sound rebounding around that enormous church they record in. (And occasionally it does). But even more, I was hoping with fingers crossed Wilson wouldn’t ask them for that ridiculous vibrato. Can we just get through one piece without it? The answer is - not really. Nevertheless, I ended up enjoying this piece very much (even though it is quite long). It conjures the soundworld of Scriabin and I was instantly drawn into its awesome, alluring aural landscape. The quartet of strings is placed in front, but not unnaturally so, with the tutti strings sometimes a bit indistinct and wooly back behind them. But it isn’t too serious, and later, they sound gorgeous in con sordino passages. As I was relishing the expressive solo violin playing of concertmaster Charlie Lovell-Jones, I quickly noticed his vibrato can get awfully fast and nervous at times, which makes me now wonder how much of what I hear from the full section is actually coming from him - perhaps emphasized by a too-close microphone. Or more likely, encouraged too much to go too far by the conductor. But he just keeps it in check here in his soloistic passages, producing a shimmering silkiness which is lovely to listen to. As it went on, I noted impressive dynamics (especially on the loud end - typical of John Wilson), but also a bit of congestion in the bigger, most intense tutti passages, swamped in the reverberation. Elsewhere, though, textures lightened beautifully - the enormous hall enveloping the sound with a cushion of air over bowed textures and golden richness, with some positively sumptuous string sound. Taking a break after this, I came back on a different day to listen to Enescu’s substantial, very long (almost 40 minutes!), very Richard Straussian Octet, in this version (approved by the composer, though with instructions) for full string orchestra. And I was quite simply blown away. What an incredible, moving piece of music. And Wilson is quite simply magnificent in it. However… (and you know what’s coming) It begins with drama - passionate soaring lines, vibrant solo violin and viola in animated conversations, and rich rhapsodic tutti passages. Wilson excels in this kind of music, bringing out the endless variety of moods, emotions and energy levels without becoming too melodramatic. This opening movement is very long (nearly 13 minutes), but it doesn’t feel that way. Wilson keeps it moving - both propulsively and emotionally - finding light and shade textures as he increases and then eases the drama. And he gives the solo cello plenty of time for a heartfelt moment of reflection in the central section, which is very moving indeed. And this string section once again demonstrates it is one of the very best - enormously impressive in its responsiveness, quickfire dynamic swings, and amazing variety of vibrato speeds. And about that vibrato, it gets very, very fast in places, adding overwhelming tension. And the violins become practically hysterical at times - screaming (almost screeching) at the heights of ecstatic intensity. I’ve never heard anything quite like it. And they’re not done yet. The Second movement is vigorous and Wilson elicits some impressive, incisive bowing from his players. But it’s not quite hard-driven (which is good). He brings some delicacy and lightness here and there, at least until the final section, where he just can’t help himself and drives it home hard. However, (and here it comes), as this movement progressed, I became increasingly concerned as these violins grew more and more agitated, getting overexcited and frenzied, and their vibrato gets faster and faster and eventually absolutely frantic. (And once again I’m hearing it predominantly from the 1st desk of violins. Why are they doing that? And why is the engineer highlighting it?) Ultimately it becomes ridiculous. However, I wasn’t as bothered by it here because Wilson is whipping up such a frenzy from the entire ensemble, the violins are really working hard to remain the center of attention. Musically I can just barely accept it in this context, but I do wish they wouldn't go berserk with it. Moving on to the Lent - it is, in a word, lovely. Too long, yes, but Wilson keeps it moving and does his very best to make it sing - at times with a delicate sweetness, and others with passion but not heaviness. I was surprised to discover this piece was composed some 45 years before Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen - it sounds so much like it I would have expected that Enescu had been strongly influenced by it. But it’s the other way around! The Lent crescendos into the finale without pause, establishing a vigorously rhythmic Valse, consistently ebbing and flowing in intensity and mood. Wilson’s way with it is splendid - and the vibrato is kept in control until about the 6-minute mark, where the easily excitable violins simply can’t contain themselves any longer and the hysterical screaming heard in the 1st movement makes an unwelcome return. The piece ends with ferocity and frantic intensity, leaving one rather exhausted and emotionally drained. Despite its length, this is undeniably a fantastic piece, brought vividly (and vigorously) to life by Wilson and his incredible orchestra. The Chandos recorded sound is excellent too - a bit more forward (but not too much) and better focused than in the rest of the program, to great advantage. (The booklet reveals it was recorded at a later session than the rest.) I do think Enescu's Octet should have come last on the program, and perhaps beginning with Bacewicz’s energetic concerto, which would have been a splendid concert opener. But that’s a minor quibble. In the end, this a fantastic program of music. And other than my constant irritation with the vibrato, this really is a sensational album. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed